By Micheal McOuat (Operations Coordinator for Volunteer Alberta)

Over the last few years, Volunteer Alberta has been exploring the concept of Inclusive Engagement by asking how organizations can support diverse volunteers, create equitable opportunities, and foster meaningful connections across Alberta. This work is part of our broader (un)learning journey to understand and integrate Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Social Justice (IDEAS) into our services, programs, and internal practices. This has been an iterative process, shaped by community conversations, support from our network, and internal reflection. One concept we have kept returning to is intersectionality.

Coined by civil rights advocate Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality describes how different forms of inequity interact, and how a person’s identity is shaped by those multiple, overlapping factors that can compound one another1. In 2022, thanks to our summer student Celeste Kwok, we were also introduced to the idea of Intersectional Healing2. This is a framework that builds on the concept of segmentation of identities to foster overlaps across communities, allowing for a nurturing of understanding and collective regrowth. Together, these ideas remind us that to build healthy communities, people need to feel seen, heard, and understood within the richness of their identities and how they experience the world.

With that, welcome to the second installment in our Constellations blog series, where each post serves as a unique star, illuminating the intersections of identity, culture, and society. Through this series, we hope to offer insights into the many ways volunteerism and civic engagement manifest across our diverse province. By embracing the complexities of our diverse communities, we can better understand the importance of our connections and the rich tapestry of the human experience.

Tansi

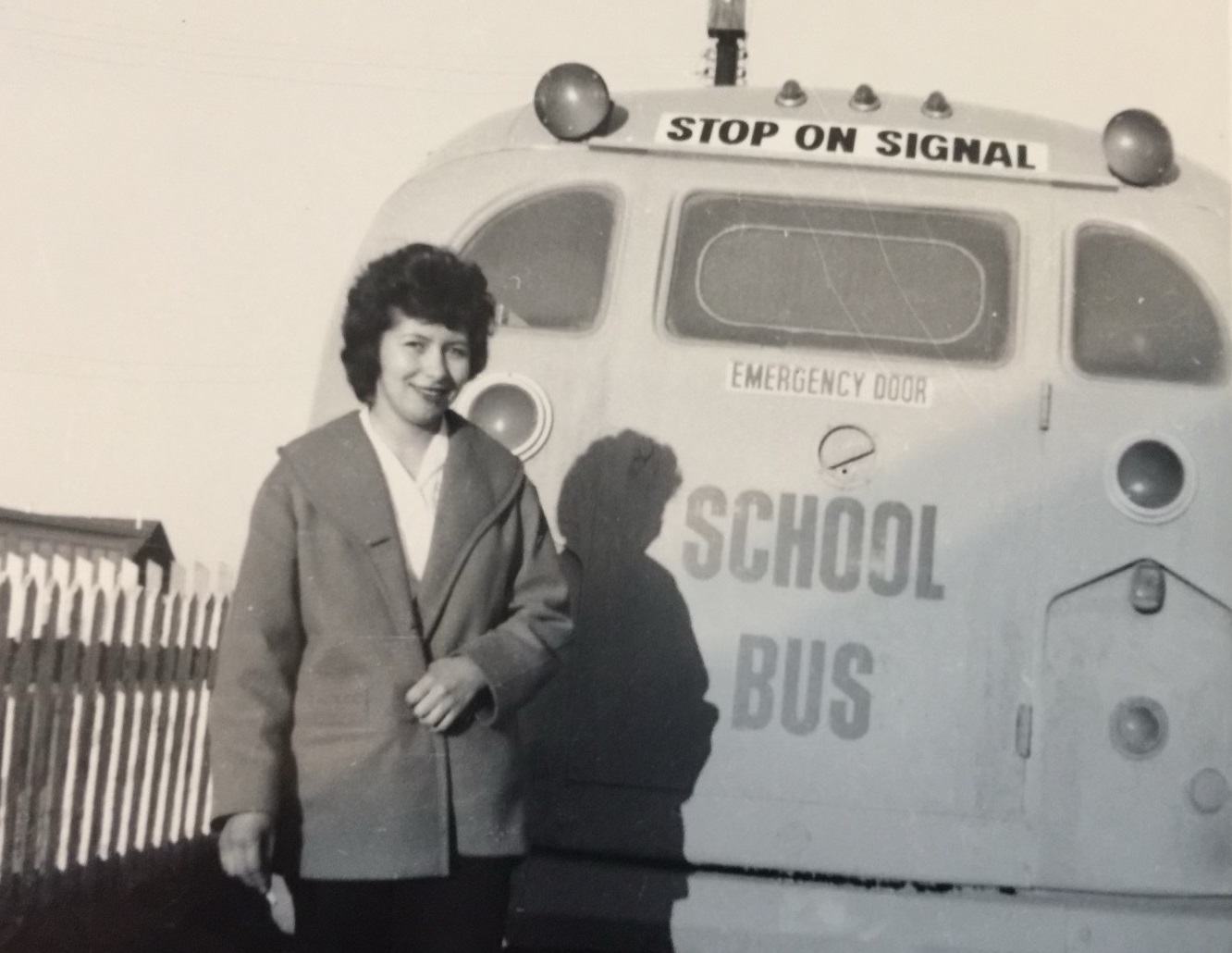

Joyce Parenteau was born in Paddle Prairie, a Métis Settlement in Northern Alberta. She’s been deeply involved with her community for decades—as a schoolteacher, a member of the Métis Settlements Appeal Tribunal, and a contributor to countless boards and projects. Today, she continues her work as part of the Elders Wisdom Circle for Children’s Services and an Elder for the Manning Métis Local.

She’s also my grandma.

Grandma Joyce and I share a lot in common—our love for handwritten letters, gardening, and fiddle music (although both of us would admit to having no musical talent whatsoever). We are also both proud Métis from Northern Alberta—I grew up just 45 minutes from where she did. Living close to her and our extended family helped me understand myself, my heritage, and my sense of community.

Grandma Joyce is the matriarch of our family. She’s always been a connector, taking it upon herself to make sure everyone is doing okay. No matter the distance, in relations or kilometers, she will drive hours to see community hockey games, bring baked goods, or just stop for a chat. I’ve always been in awe of how at ease she seems in this role.

When I asked her why she’s always on the move, she simply said, “Being connected with people [was] always important to me, and it was just a way of life.” She credits her own mother for this philosophy, explaining that, “She was very creative at crafts, […] she made things, knitted, crocheted, painted, and she’d give her stuff away. She would just give it away, and I guess what’s where I’ve kind of learned […] how to help others as much as I could, when I could.”

I think I learned the same sense of responsibility from watching her and my own parents. In small communities, you rely on your network of friends and family. There’s a rich pattern of reciprocity that feels more relational than transactional. A quick coffee visit might turn into helping fix a neighbour’s tractor, which leads to a donation of manure for your garden, which then leads to a dinner invitation using those vegetables, and so on (true story—I watched those very steps happen for my dad).

When I talk to my friends who grew up in cities, I’m often struck by how different our experiences of community building are. As Grandma Joyce puts it, “Volunteerism has been a focal point of people in a small community. Being involved, whether it is for fundraising or an event or funeral or wedding or sports, people have felt the need to help out other people because that’s what volunteering is all about. And we notice it more when it is a small community because people know of one another and their families.”

Different, but the Same

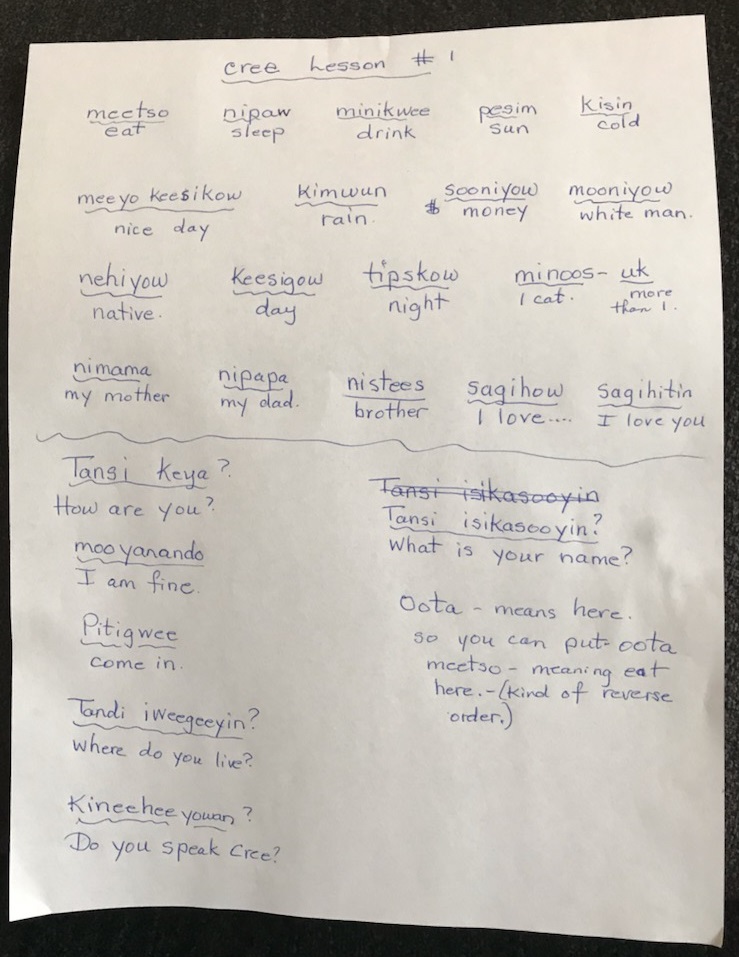

As I mentioned before, Grandma Joyce and I share a lot of things in common. Even our personalities are similar—my own family can testify to how stubborn we both can be. But we are also quite different in a lot of ways too. My grandmother’s first language was Cree (her own grandmother didn’t speak English at all), while I sadly only know a few words and phrases. She became a mother before starting her first job; I had my first job at 14. She has a passionate interest in sports, from curling to boxing, and I’m not fully confident I can define what “off-ice” even means.

Despite these differences, our views on community and responsibility are remarkably similar. As Grandma Joyce says, “You’re connected with people, and you help because they need help. Just the natural function, I think, in our life. Connection keeps our family and our community intact and, you know, being respectful and helping one another in all the different ways and things that we do every day.”

I couldn’t agree more. Disconnection, often caused by systemic barriers, can have serious consequences3. Connection, though, drives our way of life. I believe we all have a responsibility to build and nurture connections—whether it be through the many formal or informal pathways of civic engagement.

One of Grandma Joyce’s greatest fears is the loss of culture as a result of disconnection. “It’s about the cultural teachings, [our] cultural heritage and one of them being the language. And we’re slowly losing that, and we have to gain it back.”

I was fortunate to grow up so close to my community and learn from my grandparents. Many Indigenous people, disenfranchised by colonial systems, haven’t had that opportunity. I was also lucky enough to have an Indigenous teacher in high school. Unlike many my age who graduated in 2009 and earlier, I was taught about Residential Schools and the impacts of colonization in my high school curriculum. But it’s thanks to community builders like these and the growing empowerment of Indigenous communities that things are changing for the better.

“I’m happy to say that a lot of the schools in the northern part here […] they have cultural teachings and lessons in school.” Grandma Joyce says. “And to me, that’s so uplifting because we need to have it to continue to keep our language.”

I’m grateful for organizations like Centre for Race and Culture4 and the Outdoor Learning School5, whose programs have made a lasting impact in restoring Indigenous languages and providing cultural teachings, which I personally have benefited from, and the work that the Otipemisiwak Métis Government of Alberta6 does to cultivate connection.

A Lesson in Laughter

I would like to share a short clip of my conversation with Grandma Joyce, where we get sidetracked into a Cree Language lesson and some reminiscing. We both agree that laughter and joy are powerful ways to build connections. I hope this brings a smile to your face, and in doing so, a gentle reminder that despite our own possible differences, by reading this, you have built a connection between our two stars.

Thank you for walking with us on this journey, and we look forward to our continued stargazing.

Resources

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167. ↩︎

- Kwok, C. (2022). Intersectional Healing: Findings from community-based research with Chinese & Indigenous communities in Alberta. Volunteer Alberta. ↩︎

- Na, P. J., Jeste, D. V., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2023). Social Disconnection as a Global Behavioral Epidemic: A Call to Action About a Major Health Risk Factor. JAMA psychiatry, 80(2), 101–102. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11112624/ ↩︎

- Centre for Race and Culture. (April 28, 2018). Nehiyaw Language Lessons [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/kXp0J3geugo?si=rq0X6tC-nFfSX1lQ ↩︎

- Outdoor Learning School: Indigenous Language Learning. https://outdoorlearning.com/events/category/indigenous-language-learning/ ↩︎

- Otipemisiwak Métis Government of Alberta – https://albertametis.com/ ↩︎