By Graeme Dearden (VA Manager, Learning and Resources)

One of the most challenging aspects of playing pool, at least in my experience, is eye strain and fatigue. Pool isn’t an activity that is very hard on the body, but when you’re practicing for a few hours, it can become hard to maintain focus and form. My vision blurs, my arms tire, and my feet get slightly sore after bending over, aiming, and shooting for a while. A bit of that strain can make you start missing shots.

Pool is something I used to play in college all the time. Often, I would play on my own, shooting through racks of balls over and over while listening to podcasts and drinking coffee. I found it therapeutic to take time to focus, practice, and improve slowly at something relatively meaningless. Even now, I show up early when the pool hall opens and treat it like morning meditation.

But, I stopped playing almost entirely for years when things got busy, and I had to prioritize everything else over pool. I worked full-time in Calgary at a glass factory, while working part-time at a small nonprofit and exhibiting as a practicing artist. Combined with the sluggish pace of the public transit system and all the hum-drum chores of cooking and cleaning, I figured pool was something I could easily deprioritize to tend to all the stuff I had to do.

I think having to give up your hobbies is a sign of burnout. One can tune into many different signals to diagnose burnout, but feeling like you have no energy to engage in what you enjoy, even in the pockets of non-work time that come up any given day, is a sign. I was clearly burning out during those hectic years in ways that still impact me today. Burnout stays in your body through habits and trauma responses, which can leave you feeling exhausted even during periods of rest. I spent years training my body to feel tired, no matter what I did.

These days are a bit different. I play pool almost every weekend, sometimes twice even. I play once a week on Fridays or Sundays at the pool hall across town in Edmonton, where I live now. I do very little when I get there other than practice drills and play games of eight-ball against myself. Once a month, a coworker and I will play together, which is an excellent way for us to unwind. Ultimately, I get some time to relax by doing something no one needs me to do.

There have been several changes in my life over the years that allowed me to get back into a routine of doing something I love. Moving to a new city and working at Volunteer Alberta (VA) were big shifts for me. But I only really got back into playing pool once one key thing changed in my life.

Last year, VA started experimenting with something we dubbed Flowing Fridays. This experiment consisted of two parts:

- every odd Friday would be a day where everyone at VA didn’t take any meetings (specifically called Focus Fridays)

- every even Friday would be a day off for us to do as we please (specifically called Free Fridays)

We started this experiment with a timeframe in mind. We’d test it out for 3 months, then come back and adjust if needed based on evaluations performed with the whole staff team. There was a little hesitancy at first, with some folks wondering if this would be feasible given their workloads, but overall, there was appreciation and support for the idea in the air.

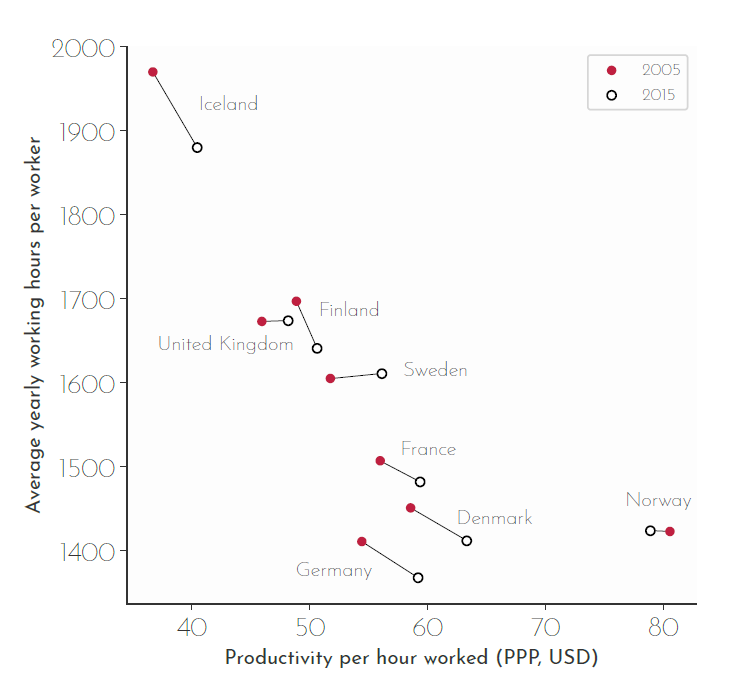

There’s a lot of support for the idea of four-day workweeks worldwide. Looking at Iceland’s large-scale experiment with four-day workweeks in 2015 reveals a strong correlation between shorter working hours and increased productivity. These factors are indeed mediated by other factors such as general technological and industrial development, investment, equality, available part-time work, and so on. Still, there remains a noticeable tie between shorter working hours and productivity.

Now, it’s easy to look at Europe and conclude that their success in testing progressive policies like four-day work doesn’t mean there will be success in other regions of the globe. But on the other side of the world, four-day workweeks have also been shown in the US to lead businesses towards improvement in staff morale, retention, and quality of output, according to a white paper published by Coulthard Barnes, Perpetual Guardian, The University of Auckland, and Auckland University of Technology (AUT). Case studies have also been collected by 4 Day Week Global, illustrating the concept works across the planet in the US, Australia, Ireland, and more. And the idea has even worked well in Japan, with Microsoft testing a four-day workweek for the company in Japan and seeing a 40% increase in productivity during the experiment.

Here in Canada, we just finished our first-ever pilot program examining the feasibility of a four-day workweek. The evidence of its impact is pretty straightforward, as 100% of participating organizations decided to continue with a four-day workweek after the experiment’s conclusion. This experiment showed that reduced working hours could increase productivity and overall organizational revenue, so it’s no wonder they kept with it. We’ve also seen numerous notable organizations embrace the four-day workweek due to the mounting evidence that it supports positive outcomes like increased ability to attract talent, improved staff retention, increased happiness, and decreased stress. Volunteer Alberta is in good company with organizations like Imagine Canada, pipikwan pêhtâkwan, Greenpeace Canada, David Suzuki Foundation, Eco Superior, and Impact Organizations of Nova Scotia.

All this existing research led the Volunteer Alberta team to discuss implementing a four-day workweek at our organization. We discussed a few different options, but ensuring we had a team discussion before making any decisions was crucial. In my experience, seeing other organizations implement four-day work weeks, one of the biggest stumbling blocks can be not appropriately planning and preparing staff for the change. Volunteer Alberta took an approach that prioritized research and evaluation so we could accurately judge the results of our experiment.

So, the leadership team at Volunteer Alberta tried its best to ensure we consulted with the team before the test. We spent time hosting discussions with the rest of the team about potential iterations of the test, talking to our external HR consultant, and gaining consent to run this experiment. Even after all these discussions, we wanted to also make sure the team knew this wasn’t a permanent change until we knew it was working as intended.

Our data from the first leg of the test (July 2022 to September 2022) was interesting. Within the first five weeks of the project, we didn’t see quantitative data indicating a strong positive or negative impact. If anything, the data suggested that switching to Flowing Fridays did not make it harder for staff to complete their tasks and didn’t notably increase or decrease stress at work. However, our surveys to measure this data could have been better due to a low response rate, so in subsequent weeks and months we decided to dive deeper with qualitative data. Through internal meetings with the operational team, the leadership team responsible for implementing this experiment found that staff had various opinions about the experiment.

Staff felt like they were more cared for by the organization. And as a result of Flowing Fridays, people reported their mental health improved, their overall energy was more positive at work, they could complete the same amount of work as before, and the timing of having a day off every two weeks seemed ideal. Additionally, the time off allowed people to pursue community-based activities, volunteering, day-to-day chores and appointments, hobbies, and (maybe most importantly) rest and relaxation.

In short, this experiment with four-day work weeks allowed staff a bit more time and flexibility to live their lives how they see fit.

I want to take a moment to reflect on how important that is. The kind of burnout I experienced at work in the past is not uncommon. And, of course, our mental health directly impacts how we do our jobs. But, the successes of the four-day workweek across VA and other organizations can’t simply be measured using metrics like productivity and job performance. The four-day workweek is a change that needs to come from a place of shared humanity and community care.

Hearing stories of burnout worldwide and how insidious modern work culture is can be chilling.

And in my mind, one of the most potent pieces of evidence that the experiment was working as intended was when people felt like their mental health had improved and that they were not burning out. But, further to this point, when we make small changes in how we work, like Flowing Fridays, we have the power to instill some degree of empathy and care into the modern work landscape. For example, something I have been vocal about during this experiment is that we don’t frame Flowing Fridays as part of people’s benefits package because this reframing of work culture must come from a place of creating new norms. In the same way we don’t claim that weekends are part of an employee’s benefits package because it’s just a standard we expect as a community; we should also frame four-day work weeks as a new standard of care for employees.

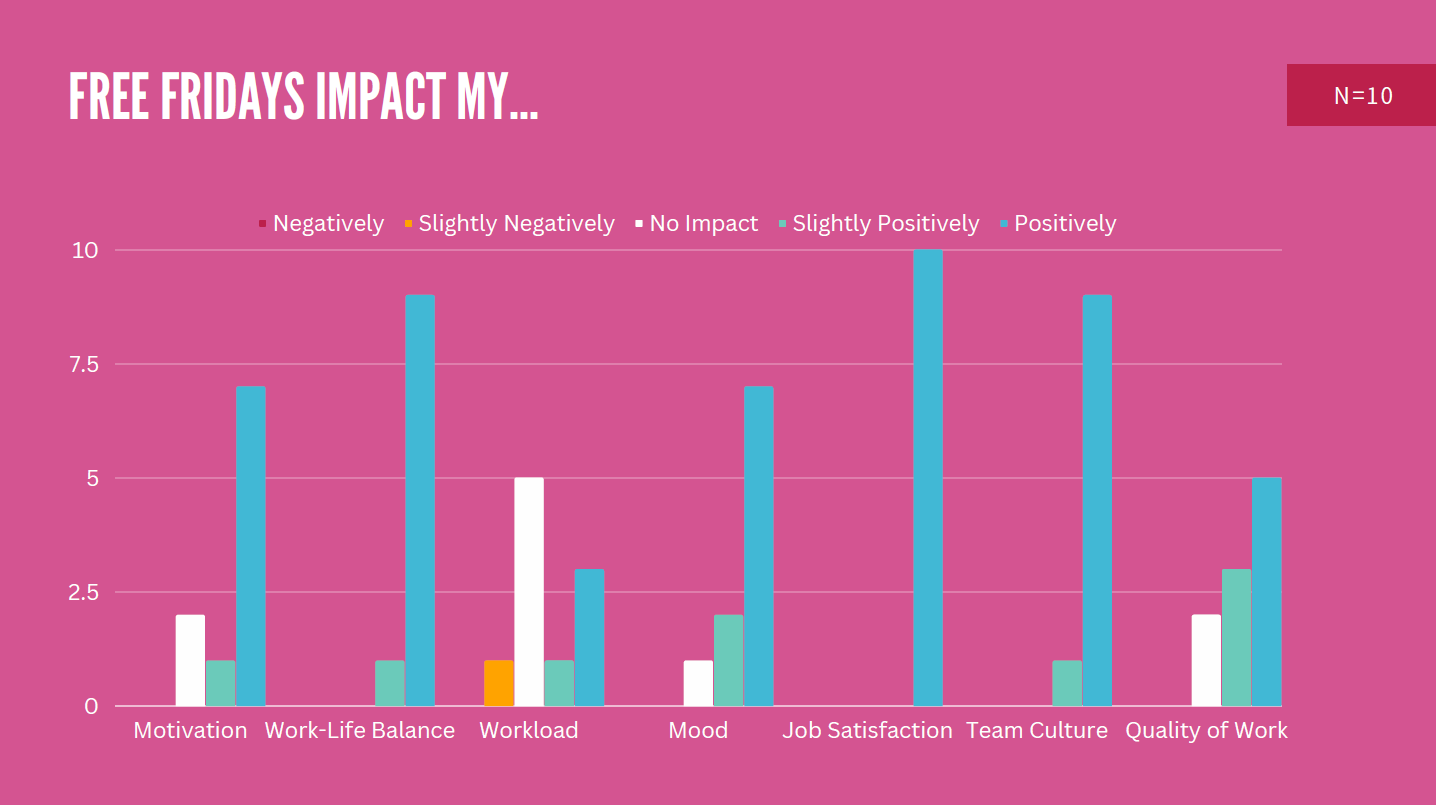

As the experiment continued from September 2022 to June 2023, we saw even more positive trends emerge as outlined in our first intern learning brief for the project. People reported feeling a sense of pride in working for VA when talking about their work with family and friends. And the quantitative data we received from folks showed a very positive correlation over time between having every other Friday off and increased motivation, mood, team culture, and quality of work. And in the long term, people continued to feel improvements to their satisfaction in their jobs and work-life balance, with some folks remarking that the extra day helped them feel re-energized.

One person did note, though, that they felt their workload was slightly negatively impacted by Free Fridays. This made me think it’s essential to remember that these kinds of experiments are a privilege for organizations like VA. I’ve personally spoken to other organizations who have attempted to implement four-day work weeks with a staff team that already has more work than they can handle in any given week. With these organizations, they had issues where people didn’t stop working on their assigned days off because they knew there was too much for them to do. Suppose there’s no attempt to mitigate workload in the first place by addressing some of the root causes of burnout, like urgency culture, unreasonable deadlines, and top-heavy hierarchies that deprioritize operational staff. In that case, four-day work weeks might not work exceedingly well.

But for VA, the results have been very positive, and we are trying to make sure we share our success in this experiment with the rest of the world. We don’t want to come off as self-absorbed by publicly sharing the results of an internal experiment. Still, as a provincial member association, we genuinely believe we can set a good example of a path to more equitable and human-centred employment in the social impact/nonprofit/voluntary sector. We want to say to the rest of the sector, “This is possible!”

Looking at the results above, it’s no wonder the staff unanimously supported continuing Flowing Fridays permanently after June. It simply makes sense for us. The research from around the world provided us with more than enough reason to try something new, and we designed a version of the four-day workweek that struck an equilibrium between our work and personal lives. I think, just like after a good session of shooting pool, the time off gives us a chance to rest and refocus our vision and bodies so we can come back to the table refreshed and ready to play another game.